There’s a scene in the film Say Anything where Lloyd (John Cusack) comes over to Diane’s house (Ione Skye) for what will emerge as a fairly high-stakes dinner with her father (John Mahoney) and his very business-like adult friends. (This meal is where Lloyd, asked what he’s going to do with his life, famously declares his personal philosophy: he doesn’t want to buy anything, sell anything, or process anything. The party ends with the IRS showing up to investigate Diane’s dad for tax fraud.)

Diane’s not ready yet when Lloyd arrives just before all that; he awkwardly pokes around her bedroom as she holds out various dresses around the closet door and asks his opinion on what to wear.

He pauses at a thick reference book, stroking its spine. “This is a mother dictionary,” he says, just loudly enough for her to hear.

“I’ve had it forever,” she says. “I used to have this thing with marking the words that I would look up.”

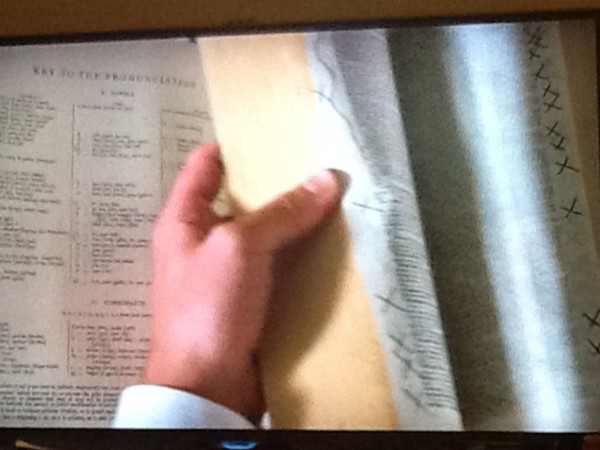

He flips through the pages, slow at first and then faster, running his finger down columns where nearly every word has a ballpoint-pen X beside it in the margin. Sometimes she’s marked whole runs of words with a giant bracket.

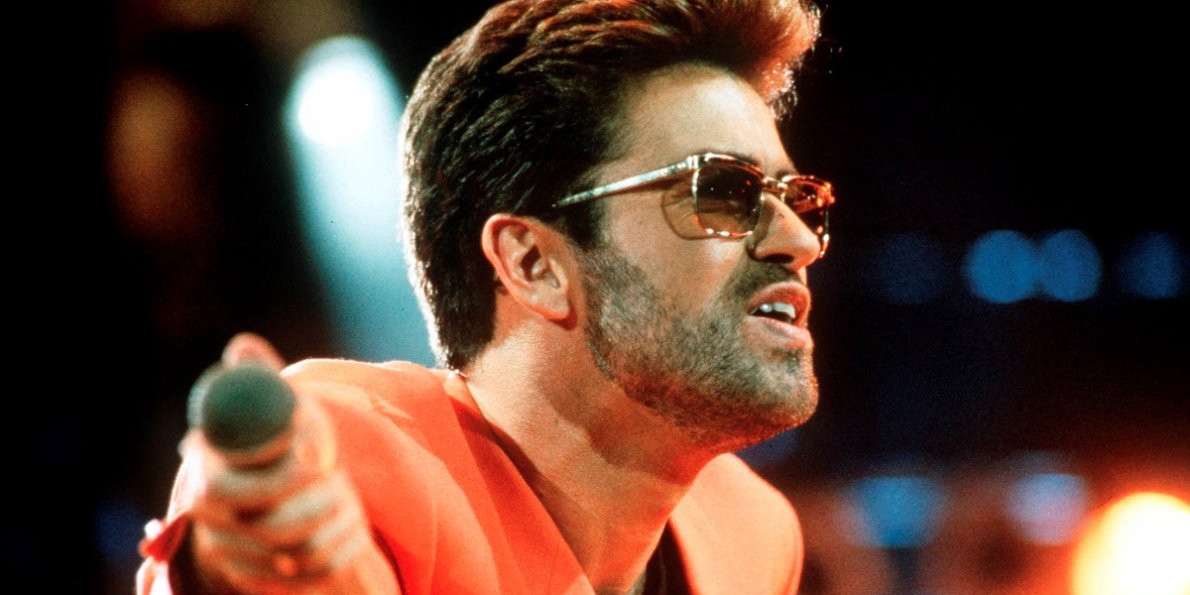

Diane was the valedictorian of a class where Lloyd may have been considered, by at least a few, the coolest dude around. He possesses a shy confidence that is painfully, obviously undercut with a heavy streak of slacker self-doubt.

Lloyd slams the dictionary shut. Maybe he’s overwhelmed, maybe impressed, or maybe both. She emerges with yet another dowdy, matronly dress option and he smiles as if it’s the sexiest thing he’s ever seen. They go down to dinner.

Of all the many times in Say Anything that we are shown and told that Diane Court might be the smartest 18-year-old girl in Seattle, and that unbelievably this is why cool guy Lloyd is in love with her, or at least the idea of her, this has always been the one that stuck with me. She’s undeniably a nerd—“trapped in the body of a game-show hostess,” as one of Lloyd’s female friends observes—and he undoubtedly likes her more for it.

I never had a dictionary quite that fancy growing up—I don’t have a strong memory of any given edition—but from early as I can remember, I would ask my mother what a word I’d come across in a book or newspaper article meant and she would answer, “Why don’t you look it up?” In high school, I had an otherwise unbearably old-fashioned English teacher one year whose most common-sense lecture on a similar topic somehow stuck, habit-forming in its simplicity: Don’t ever read past a word you don’t understand. Stop and look it up. I longed for the luxury of having a dictionary so comprehensive and yet so commonplace that I could mark X’s in pen like Diane’s. I wished for some way to document retroactively how many words I had researched, that I knew.

After my father’s parents died, I came home from college to Reno for a long weekend to help him clean out their two-bedroom apartment. I left with two main inheritances: first, my grandmother’s costume jewelry collection, the kind of heavy rhinestones and elaborately set pieces that no one makes any more. (We each wore one of the necklaces for our wedding.) The other was boxes of books and LIFE magazines—nothing particularly rare or valuable, mostly cheap paperback editions of American classics, some annual calendars or notebooks or other printed giveaways that must have come with the membership dues my progressive grandparents paid to left-wing organizations through the years.

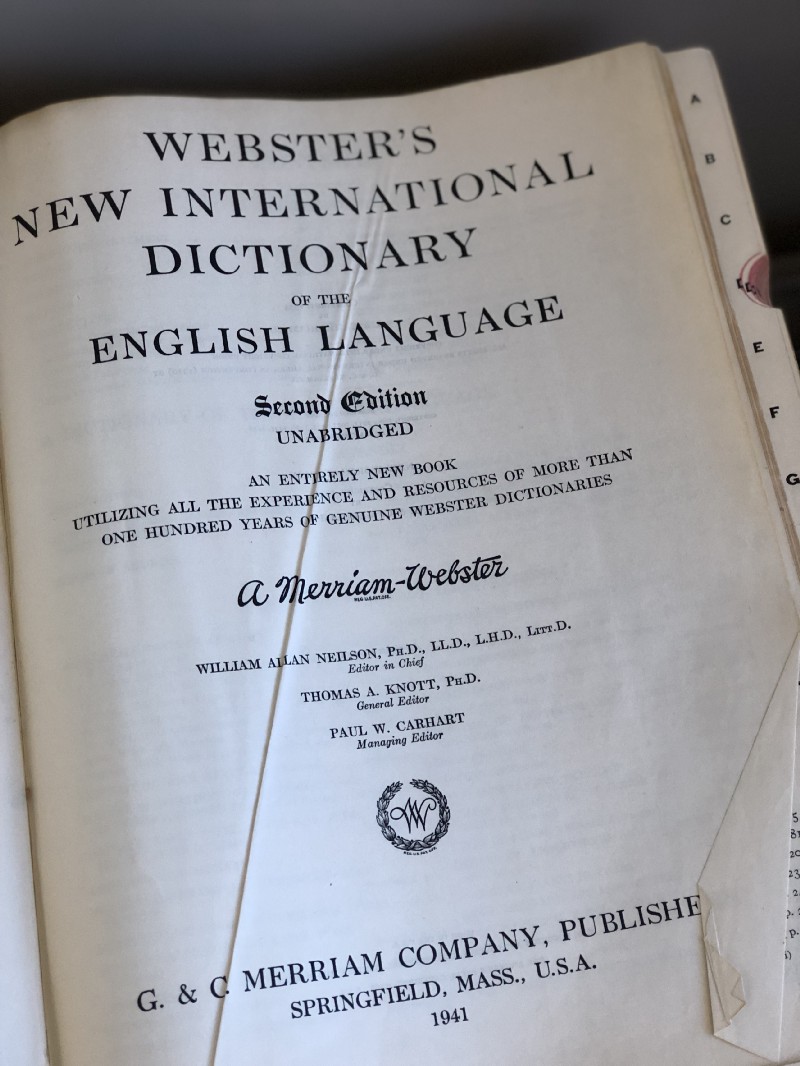

And, most greedily claimed though my only real competition, my brother, was not even there—one giant unabridged Webster dictionary from 1941, the year my father was born. It weighs at least 10 pounds and for more than a decade I hauled it, at no small expense, as I moved from apartment to apartment, coast to coast, where generally it sat on the bottom shelf of any bookcase I deemed sturdy enough to hold its bulk.

When I first moved into my current office, in a sleek shiny building in Burbank, I had a very retro-style bar along the glass window. A year later, nixed by HR, I had a mirrored bar cart I couldn’t entirely bear to bring home in defeat, so I hauled the dictionary to work and cracked it open along the top tray.

I am an editor in chief, I thought, and no matter how many types of media, how many platforms that job now encompasses, I am at heart a woman of words. Here are so many words. Let’s not forget how important each and every word we choose still can be.

Last month, for no real reason except a sudden surge of restlessness, I went over to my dictionary and took a slew of close-up photographs of the cover, the spine, a series of pages at not-quite-random inside. I also found a full sheath of newspaper clippings and typed notes and reference materials tucked inside, a haul rich enough for its own post.

Then I looked up the word that many adults I know will say was their first furtive attempt to confirm via a dictionary, particularly one in a library they might leaf through otherwise anonymously, that they might exist in some older, more recognized form: homosexual.

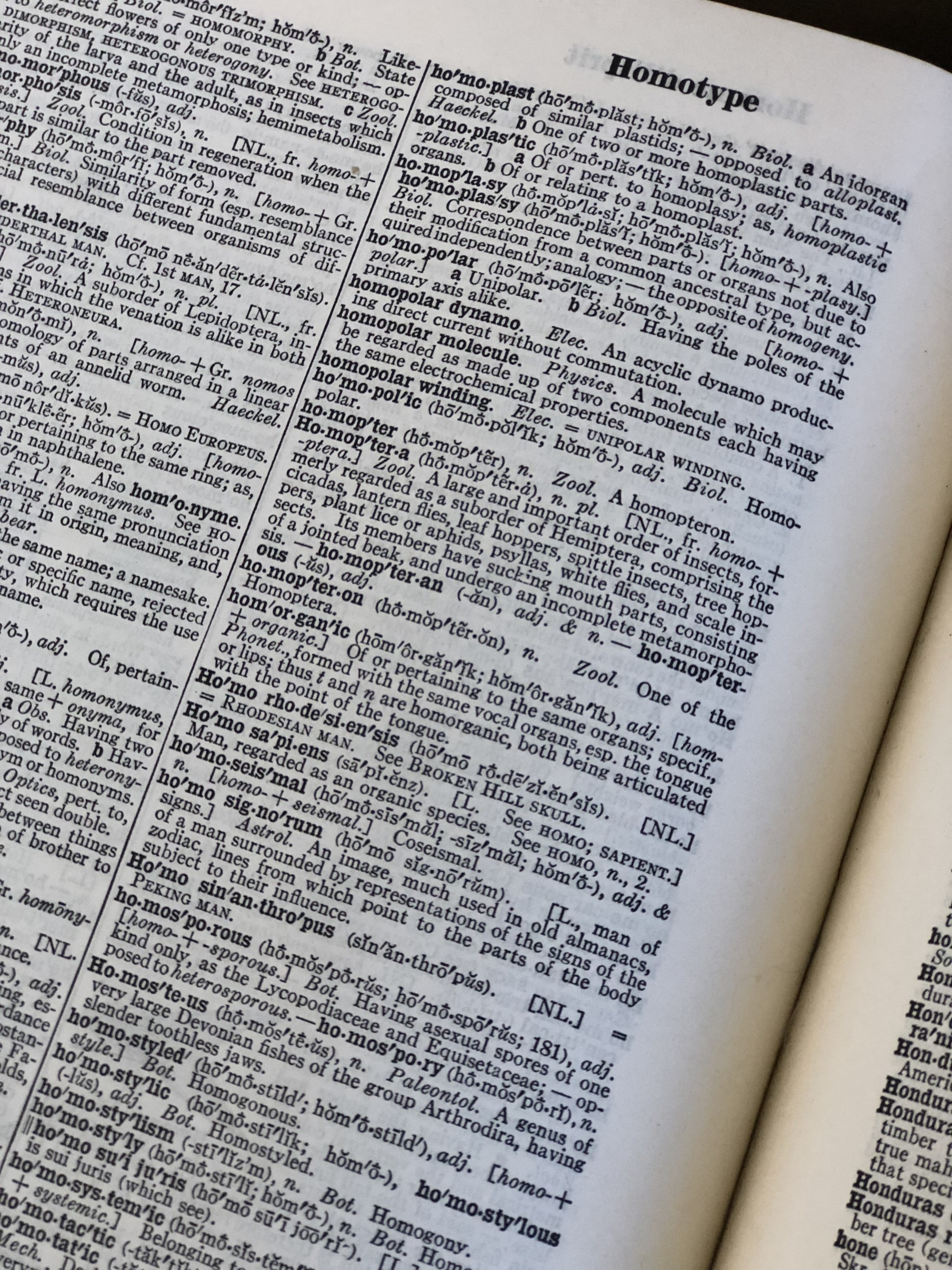

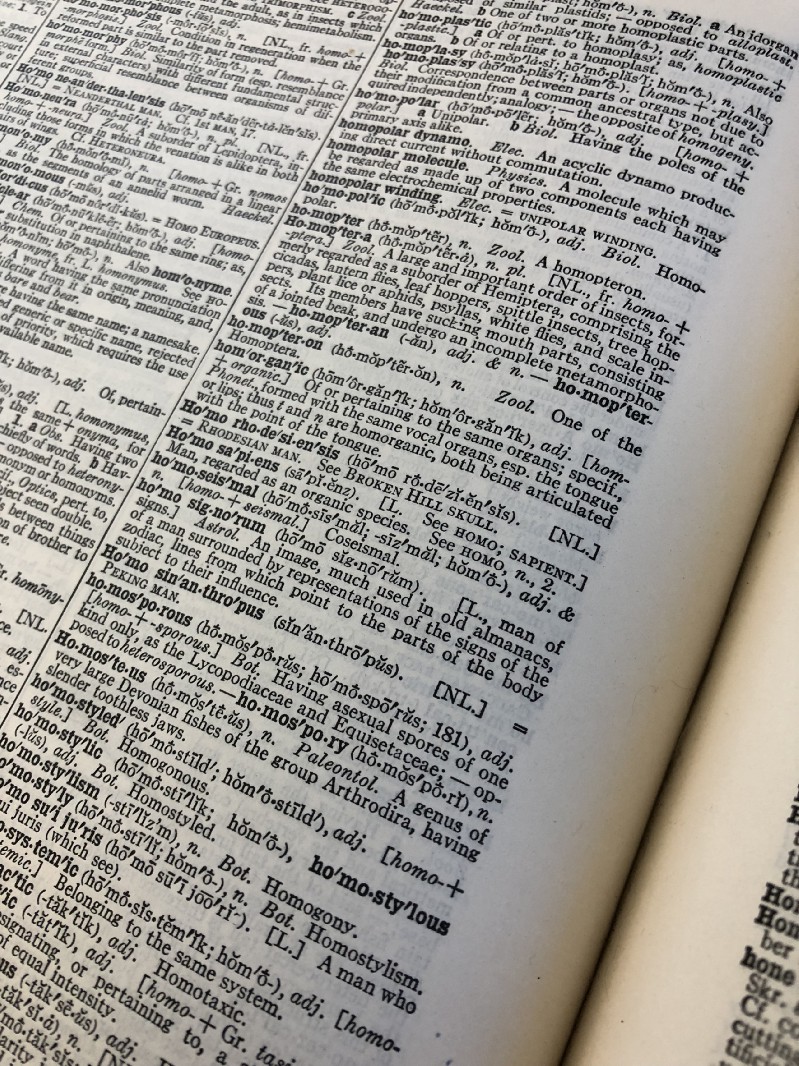

But the 1941 unabridged Webster’s does not include the word homosexual, or any of its variations.

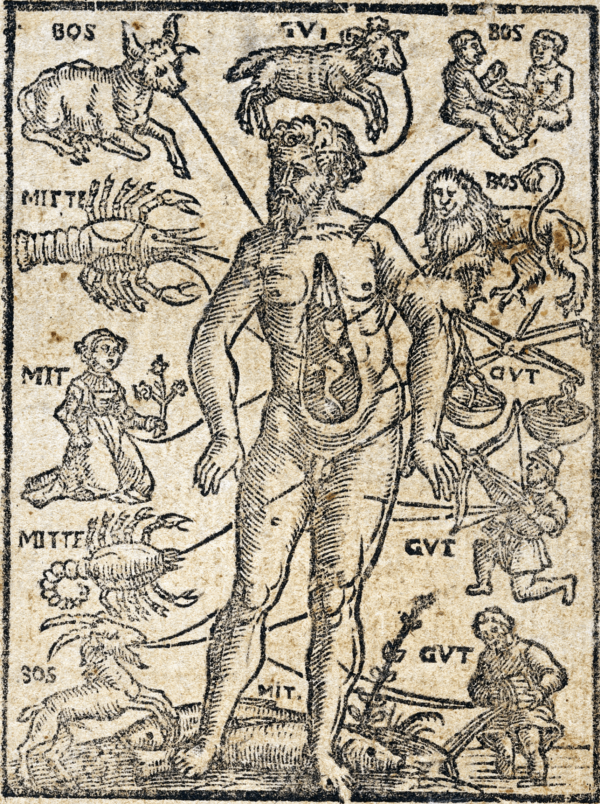

It skips from Homo sapiens (“Man, regarded as an organic species”) to homoseismal (“Coseismal,” which according to m-w.com means “simultaneously affected by the same phase of any particular seismic shock”) to homo signorum (“An image, much used in old almanacs, of a man surrounded by representations of the signs of the zodiac, lines from which point to the parts of the body subject to their influence”).

I have no idea why homosexual is not included in this dictionary. Their website now includes the definition—“1. of, relating to, or characterized by a tendency to direct sexual desire toward another of the same sex; 2. of, relating to, or involving sexual activity between persons of the same sex”—and notes the first known use of the word was in 1891. There’s no detail on the site given on when or why it was added to Webster’s lexicon. (Just looked up lexicon to be sure I was using it correctly; according to Google it is “the vocabulary of a person, language, or branch of knowledge; a dictionary.”)

That’s not to say no one could tell me why it’s not included. Here’s one lengthy and fascinating longread about the history of Merriam, Webster and all their editions and additions, which leads me to believe that I could likely get a human on the phone who is perhaps willing to take me down that particular queer rabbit hole.

A quick google (the verb, using the proper noun site, and also the clear antagonist in this dictionary ecology) reveals that in fact earlier Webster’s did include the H-word, perhaps before my edition: In 1909, according to OutHistory.org, homosexuality made its debut in Merriam-Webster’s New International Dictionary “as a ‘Med.’ (medical) term meaning ‘morbid sexual passion for one of the same sex.’ Homosexuality was considered a ‘morbid’ (diseased) passion because it was not a passion for procreating, but for sexual pleasure.”

The site also says heterosexuality didn’t make the page until 14 years later, in 1923, when it was similarly defined as a “morbid sexual passion for one of the opposite sex.”

Here I believe this site may be quoting verbatim from historian Jonathan Ned Katz’s The Invention of Heterosexuality:

In 1934 “heterosexuality” appears in Webster’s hefty Second Edition Unabridged, defined in what in 2015 is still the dominant modern mode. In 1934 “heterosexuality” is a “manifestation of sexual passion for one of the opposite sex; normal sexuality.” Heterosexuality has finally attained the status of norm.

In the same 1934 Webster’s, “homosexuality” has changed as well. It’s simply “eroticism for one of the same sex.” Both terms medical origins are no longer cited. Heterosexuality and homosexuality have settled into standard English.

If I could find my copy of Katz’s book, which I know at one point I definitely owned, or had ready access to his archives in the New York Public Library, I might find what appear to be further detailed footnotes about Katz’s own correspondence with a M-W rep named Brett P. Palmer on the subject:

Mr. Palmer assures Katz that “homosexuality” and “homosexual” appears on page 1030 of the 1909 edition of Websters’s International Dictionary. He also says that “heterosexuality” first appears on page xcii of the 1923 supplement of Webster’s New International Dictionary, and that the contemporary definition of “heterosexual” first appears in the 1934 Second Edition of Webster’s. Katz is grateful to Palmer for this information and for photocopies of these pages, now in the Katz Collection, NYPL.

But what of my 1941 copy?

The answer may partially be that it’s technically a Webster’s second edition, which according to the Slate longread is mostly now remembered for being something of a layover between the early origin myth-type tomes and the modernized, more curated Third:

The Second was what one Merriam editor calls the Internet of its time: 3,350 pages long, with more than 600,000 main entries, including proper nouns, and hundreds of pages of biographical, geographical, and literary appendices and other encyclopedic matter. The Second was designed to be a single-source reference for the educated classes and an aspirational text for the masses. It contained long lists of popes and dukes, and hundreds of illustrative quotations from the Bible, Shakespeare, and Dickens. But there was no mention of Mae West, Eugene O’Neill, or Babe Ruth. Popular culture, a term dating to the 19th century, was considered too unrefined for such a serious work. The Second was also priggishly didactic, prescribing what its ivory tower editors and consultants considered “proper” language, and brusquely dismissing usage that was, as its labels declared, incorrect, improper, or illiterate.

I am not sure if I should take the homosexual’s exclusion from such an encyclopedic volume as priggish (self-righteous) or perhaps prudish or simply proscriptive: if you don’t define someone, they can’t disrupt your world order, or so you might hope.

Really it was already too late for that. In 1941, homosexuals were fairly well-defined, medically speaking (if not well-described or well cared for as humans in those medical worlds). We were living in varying degrees of secrecy or boldness, particularly as the second edition of a U.S.-involved World War provided ever more freedom for independent women or sea-faring men to find each other in circumstances where perhaps many people cared more about simple survival than who kept each other warm.

I like looking this sort of thing up. It’s how I almost ended up going to graduate school to study queer history, though instead I just jumped feet-first into what they call the first draft of history, aka journalism. (My baby brother went full historian, which is almost as satisfying.)

I particularly like that we live in a world now where in order to learn a word you don’t have to skulk into the corner of a library, under a bank lamp or the watchful nosy eye of a small-minded, small-town busybody. (I never knew a librarian who wanted anything but to encourage reading more, but it can hard to differentiate gatekeepers from nurturers when you’re simply scared of defining who you are.) I like that there’s no one authoritarian answer to what a word means, though I worry like any good left-winger about the undue or unchecked influence of a google or the likelihood of instead some kid stumbling onto a site that perverts curiosity to inspire shame. I love so much that the young people who work for me delight in disappearing down a spiral of Wiki, YouTube and any other primary source they can get their hands on to learn about some incredibly specific phenomenon or sub-culture or person, going from unknown to expert in a matter of hours.

And for all that I love words, I love how they keep changing, and how these institutions, no matter how much more modern, still struggle to keep up. In 2016, Merriam-Webster added cisgender, genderqueer and the gender-neutral title Mx., according to this tweet and then this contentious, cautionary article in the MetroWeekly. None of those words are in the most wispy aspirations of my ancient history edition.

But so, so many other words are. I’m still not sure what to make of them, what to do with them. Should I pick a new word—at random? at my fancy? at yours?—and write or say something about it each week? Should I post pretty pictures to Instagram of the most unlikely or forgotten? Should I stop obsessing over individual words as a means of procrastination from writing a whole book of them strung deliberately together?

Clearly I’m willing to take suggestions or requests. What is the one word you would, or have, look up first?